- Polder from the air

To keep the major shipping route Berlin — Stettin (Szczecin) navigable for larger cargo ships all year round, to improve the yield of agriculture in the Oder Valley itself and the drainage for the Oderbruch further south, was the beginning of the 20th century that was largely unobstructed by humans Odertal redesigned according to Dutch plans. Several wet and dry polders were created.

The Dry polder, for example the Friedrichsthaler Polder (5/6) (650 hectares) or the Lunow Stolper Polder (1,680 hectares) are so-called dry polders, which means that they are protected from flooding by dikes all year round and can also be used for agriculture all year round. The so-called Wet or flood polders, for example the Criewener polder (A) (1,644 ha), the Schwedt polder (B) (1,303 ha) or the Fiddichower Polder (10) (1,773 ha) are only protected from flooding in the summer half of the year by so-called summer dykes; in the winter half of the year, from October, the inlet structures are opened, and the then frequently rising Oder water can enter the polders and through outlet structures when the water level is low, they also flow north again. (B) (1,303 ha) or the Fiddichower Polder (10) (1,773 ha) are only protected from flooding in the summer half of the year by so-called summer dykes; in the winter half of the year, from October, the inlet structures are opened, and the then frequently rising Oder water can enter the polders and through outlet structures when the water level is low, they also flow north again. From April 15 of each year, on the instructions of the responsible national park administration, the inlet structures and, after the water has drained according to the natural gradient, also the outlet structures are closed and the water still remaining in the polder is pumped out, which is expensive and energy-intensive after the structures have been closed. As of 2015, the head of the national park administration, after many years of urging the national park association, which is practically the sole owner of the agricultural land in the Fiddichow Polder (10), will at least stop pumping there. A first success.

According to a water management feasibility study commissioned by the State of Brandenburg itself, the association also demands that the inlet and outlet structures in the Fiddichower Polder (10) also remain open all year round so that the water level there can adapt to that of the Oder in at least a semi-natural way . In the Criewener and Schwedter Nasspolder (A/B), too, the inlet and outlet structures must remain open at least until May 31 of each year, longer if possible, of course, to enable natural water conditions.

The National Park Association is also very committed to ensuring that on the Polish side the Gartzer Polder and the Schillersdorfer Polder as the heart of the cross-border International Park Unteres Oder Valley remain unused and continuously connected to the water level of the East and West Oder through year-round open gates. The Polish side of the planned restart of the technical structures, the associated possibility of regulating the water level and the agricultural use of the area to be expected as a result are rejected by the National Park Association and its nature conservation partners on the Polish side.

Historical water management

Until the beginning of this century, the Oder in the lower Oder valley was able to meander largely unhindered. As is so often the case, the Oder also showed the need to continue this up to the mouth after hydraulic engineering interventions in a stream. The drainage of the Oderbruch in the 18th century made hydraulic engineering measures necessary in the lower Oder valley in order to be able to use the lower Oder, which has very little gradient, as a receiving water and to shift the backwater further and further north to protect the Oderbruch. Because of the low gradient, the water in the lower Oder valley can accumulate in strong north winds. Onshore winds raise the level of the Baltic Sea near Swinoujscie and cause the lagoon and Dammschen Lake to be filled in by back currents. Offshore winds have the opposite effect.

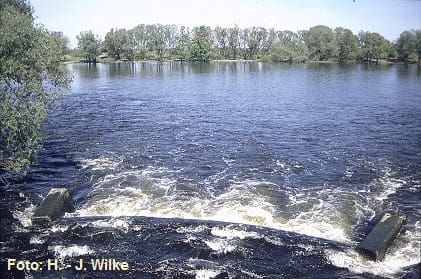

- Hydraulic engineering installation at the Fiddichower Polder (10)

Near-natural water management

- Flooding in the Lower Oder Valley National Park

There is no question that the future of the Lower Oder Valley Auenational Park depends on the quality and the amount of water used in the Oder, which varies according to the season. Right from the start, the National Park Association saw its task as promoting the most natural water conditions possible in the lower Oder valley. Thanks to his many years of urging, the national park administration stopped pumping out the water, which was cost-intensive and energy-intensive, in 2015, at least 20 years after the establishment of the National Park, at least in the Fiddichower Polder (10) — a first success! After all, this requirement was already in the maintenance and development plan adopted in 1999 and was expressly qualified as feasible and sensible by a water management feasibility study commissioned and financed by the state of Brandenburg. The National Park Association had backed up its demand with an intensive land acquisition strategy, which enabled it to oblige all users to the contractually guaranteed willingness to accept natural water conditions without recourse claims. At the latest with the provisional assignment of ownership in the name of the company land restructuring in the summer of 2013, which plans practically the entire Fiddichower Polder (10) as a wilderness area (Zone I) and assigns it to the National Park Association, there was really no longer any reason to continue pumping the water out of the floodplain national park.

Water quality

The construction of new wastewater treatment plants in the Oder catchment area and the closure of some environmentally polluting industries in the Oder catchment area have led to a decrease in pollution in the Oder water and the polders flooded by the Oder water, in particular with heavy metals. Nevertheless, the pollution of the soils in the floodplain as in the wet polders is still very high. According to the current studies, the water in the Oder, in the Hohensaaten-Friedrichsthaler Wasserstraße and in the polder waters is of medium quality.

Expansion of the oder river

Apart from two smaller weirs in Silesia, the Oder is one of the last large rivers in Central Europe that have not yet been built across. This is also due to the fact that behind the Moravian gate, as a lowland river, it only has a slight gradient. Since the Oder, unlike the Rhine, is not fed by glaciers, the navigability of the Oder remains dependent on the rainfall in the Oder catchment area, especially in the Giant Mountains. This means that the Oder is not navigable on a few days because of high water and on many days because of low water. That is why the Polish side in particular has repeatedly expressed interest in expanding the Oder, combined with the hope of EU funding, currently again by the national-conservative government in Warsaw. The German side, on the other hand, is clearly more reserved. After lengthy negotiations, on April 27, 2015, the bilateral “Agreement on the joint improvement of the situation on the waterways in the German-Polish border area” was signed. The aim of this agreement is to optimize future flood discharge conditions on the border or, to ensure stable fairway conditions, especially for the use of the German-Polish icebreaker fleet, and to enable coasters to travel between the port of Schwedt and the Baltic Sea.

Schwedt high-sea port

The new Schwedt harbor is already accessible for smaller coasters today, but at the latest after the deepening of the Klützer crossing. The paper mills in Schwedt had asserted a certain need. However, in earlier planning, care was always taken to ensure that coasters could only sail as far as the Schwedt harbor and not, for example, to the paper mills’ own bulwarks located a few meters to the south. But it is precisely this direct connection that would be important to the paper mills in order to avoid costly, additional reloading with all the dangers of damage. Above all, the city of Schwedt attaches great importance to bringing the still highly deficit port close to profitability. The new, completely oversized Schwedt port was built from the ground with very high subsidies on the edge of the national park, but is still in deficit due to a lack of tonnage and is cross-subsidized by the Schwedter Stadtwerke from economically more profitable areas. Most of the port’s income does not come from handling, but from the industrial companies located in the port area. At the beginning of the port planning, the National Park Association publicly pointed out that this uneconomical investment would require subsidies for decades to come. That’s how it turned out.